George Ripley (transcendentalist) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

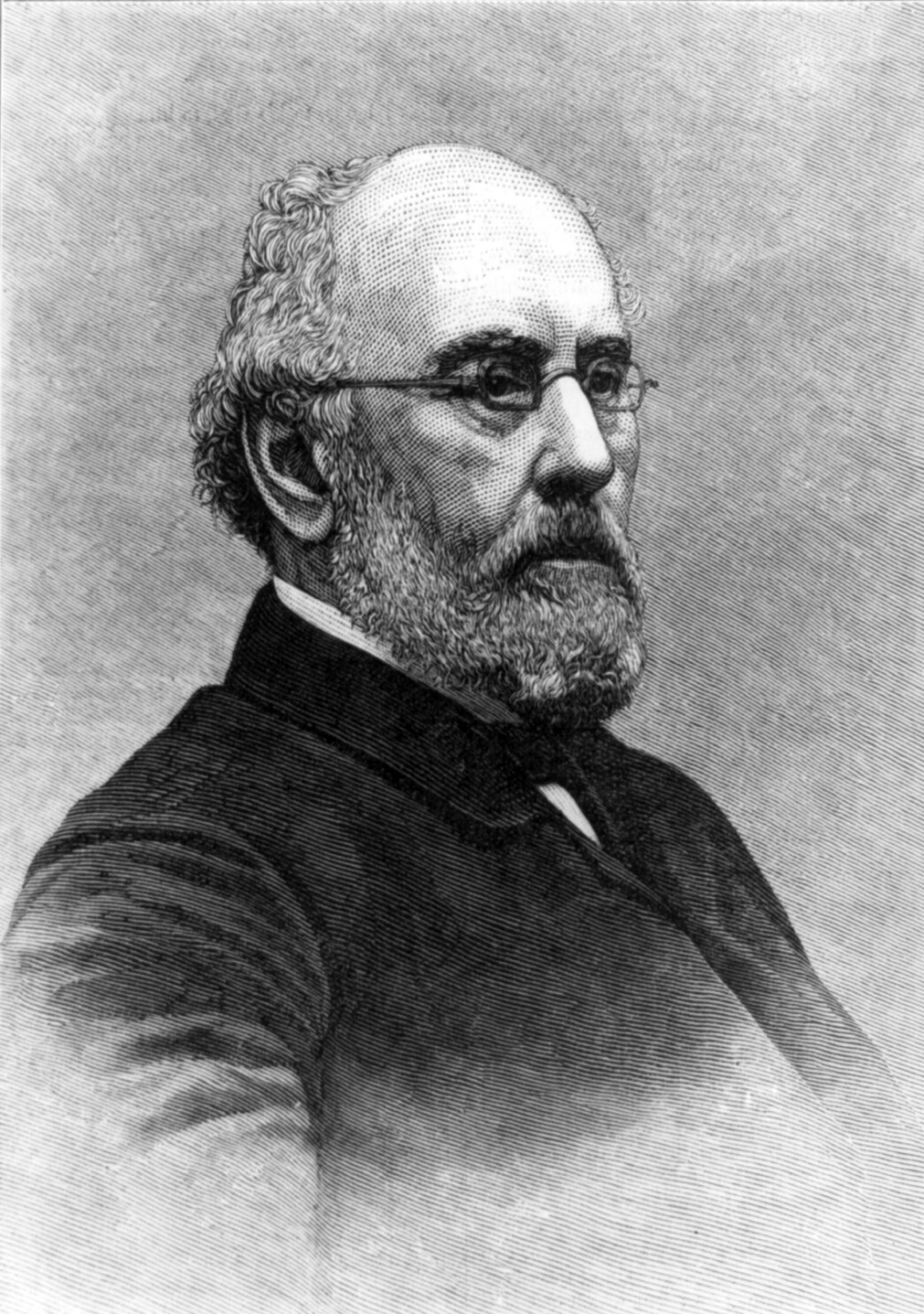

George Ripley (October 3, 1802 – July 4, 1880) was an American

After Brook Farm, George Ripley began to work as a freelance journalist. In 1849 he was employed by

After Brook Farm, George Ripley began to work as a freelance journalist. In 1849 he was employed by

George Ripley

' (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin & Co., 1882) was written by

''The American Cyclopaedia.''

From

Ripley biography

from ''Dictionary of Unitarian & Universalist Biography''

from Alcott School

from Transcendentalism Web *

Collection Guide to Ripley's scrapbooksHoughton Library

at Harvard University {{DEFAULTSORT:Ripley, George Founders of utopian communities Members of the Transcendental Club American Unitarians Harvard Divinity School alumni 1802 births 1880 deaths People from Greenfield, Massachusetts American social reformers American Christian socialists Unitarian socialists Utopian socialists People from West Roxbury, Boston

social reformer

A reform movement or reformism is a type of social movement that aims to bring a social or also a political system closer to the community's ideal. A reform movement is distinguished from more radical social movements such as revolutionary move ...

, Unitarian minister, and journalist associated with Transcendentalism

Transcendentalism is a philosophical movement that developed in the late 1820s and 1830s in New England. "Transcendentalism is an American literary, political, and philosophical movement of the early nineteenth century, centered around Ralph Wald ...

. He was the founder of the short-lived Utopia

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imaginary community or society that possesses highly desirable or nearly perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book ''Utopia (book), Utopia'', describing a fictional ...

n community Brook Farm

Brook Farm, also called the Brook Farm Institute of Agriculture and EducationFelton, 124 or the Brook Farm Association for Industry and Education,Rose, 140 was a utopian experiment in communal living in the United States in the 1840s. It was f ...

in West Roxbury, Massachusetts

West Roxbury is a neighborhood in Boston, Massachusetts bordered by Roslindale and Jamaica Plain to the northeast, the town of Brookline to the north, the cities and towns of Newton and Needham to the northwest and the town of Dedham to the s ...

.

Born in Greenfield, Massachusetts

Greenfield is a city in and the county seat of Franklin County, Massachusetts, United States. Greenfield was first settled in 1686. The population was 17,768 at the 2020 census. Greenfield is home to Greenfield Community College, the Pioneer Val ...

, George Ripley was pushed to attend Harvard College

Harvard College is the undergraduate college of Harvard University, an Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636, Harvard College is the original school of Harvard University, the oldest institution of higher lea ...

by his father and completed his studies in 1823. He went on graduate from the Harvard Divinity School

Harvard Divinity School (HDS) is one of the constituent schools of Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The school's mission is to educate its students either in the academic study of religion or for leadership roles in religion, gov ...

and the next year married Sophia Dana. Shortly after, he became ordained as the minister of the Purchase Street Church in Boston, Massachusetts, where he began to question traditional Unitarian beliefs. He became one of the founding members of the Transcendental Club The Transcendental Club was a group of New England authors, philosophers, socialists, politicians and intellectuals of the early-to-mid-19th century which gave rise to Transcendentalism.

Overview

Frederic Henry Hedge, Ralph Waldo Emerson, George R ...

and hosted its first official meeting in his home. Shortly after, he resigned from the church to put Transcendental beliefs in practice by founding an experimental commune

A commune is an alternative term for an intentional community. Commune or comună or comune or other derivations may also refer to:

Administrative-territorial entities

* Commune (administrative division), a municipality or township

** Communes of ...

called Brook Farm. The community later converted to a model based on the work of Charles Fourier

François Marie Charles Fourier (;; 7 April 1772 – 10 October 1837) was a French philosopher, an influential early socialist thinker and one of the founders of utopian socialism. Some of Fourier's social and moral views, held to be radical in ...

, although the community was never financially stable in either format.

After Brook Farm's failure, Ripley was hired by Horace Greeley

Horace Greeley (February 3, 1811 – November 29, 1872) was an American newspaper editor and publisher who was the founder and newspaper editor, editor of the ''New-York Tribune''. Long active in politics, he served briefly as a congressm ...

at the ''New York Tribune

The ''New-York Tribune'' was an American newspaper founded in 1841 by editor Horace Greeley. It bore the moniker ''New-York Daily Tribune'' from 1842 to 1866 before returning to its original name. From the 1840s through the 1860s it was the domi ...

''. He also published the ''New American Cyclopaedia

New is an adjective referring to something recently made, discovered, or created.

New or NEW may refer to:

Music

* New, singer of K-pop group The Boyz

Albums and EPs

* ''New'' (album), by Paul McCartney, 2013

* ''New'' (EP), by Regurgitator, ...

'', which made him financially successful. He built a national reputation as an arbiter of taste and literature before his death in 1880.

Biography

Early life and education

Ripley's ancestors had lived inHingham, Massachusetts

Hingham ( ) is a town in metropolitan Greater Boston on the South Shore of the U.S. state of Massachusetts in northern Plymouth County. At the 2020 census, the population was 24,284. Hingham is known for its colonial history and location on B ...

for 140 years before Jerome Ripley moved his family to Greenfield, a town in the western part of the state, in 1789.Golemba, 15 He was moderately successful as the owner of a general store and tavern and was a prominent member of the community.Rose, 49 His son George Ripley was born in Greenfield on October 3, 1802, the ninth child in the family.

George Ripley's early life was heavily influenced by women. His nearest brother was thirteen years older than he was and he was raised primarily by his conservative mother, who was distantly related to Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading inte ...

, and his sisters. He was sent to a private academy run by a Mr. Huntington in Hadley, Massachusetts

Hadley (, ) is a town in Hampshire County, Massachusetts, United States. The population was 5,325 at the 2020 census. It is part of the Springfield, Massachusetts Metropolitan Statistical Area. The area around the Hampshire and Mountain Farms Ma ...

to prepare for college. Before going to college, he spent three months in Lincoln

Lincoln most commonly refers to:

* Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865), the sixteenth president of the United States

* Lincoln, England, cathedral city and county town of Lincolnshire, England

* Lincoln, Nebraska, the capital of Nebraska, U.S.

* Lincoln ...

with Ezra Ripley

Ezra Ripley (1 May 1751 – 21 September 1841) was an American minister of Concord's First Parish Unitarian Church.

Biography

Ripley graduated from Harvard in 1776 where he taught and subsequently studied theology. In 1778 he was ordained to the ...

, a distant relative who also married the aunt of Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson (May 25, 1803April 27, 1882), who went by his middle name Waldo, was an American essayist, lecturer, philosopher, abolitionist, and poet who led the transcendentalist movement of the mid-19th century. He was seen as a champ ...

. Although Ripley wanted to attend the religiously conservative Yale University

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wo ...

, his Unitarian father pushed him to attend Harvard College

Harvard College is the undergraduate college of Harvard University, an Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636, Harvard College is the original school of Harvard University, the oldest institution of higher lea ...

, then known as a hotbed of liberal Unitarianism. Ripley was a good and dedicated student, although he was not popular with students because of his trust of the establishment. Early in his time at Harvard, he had sided with the administration during a student-led protest against poor food, and his attempts at reconciling the two sides prompted ridicule from his peers. Ripley, seeking a socially useful role, found work as a teacher in Fitchburg during winter vacation of his senior year. He graduated in 1823.

During his time at the school, Ripley became disenchanted with his father and his home town, admitting "no particular attachment to Greenfield". He hoped to enroll at Andover

Andover may refer to:

Places Australia

* Andover, Tasmania

Canada

* Andover Parish, New Brunswick

* Perth-Andover, New Brunswick

United Kingdom

* Andover, Hampshire, England

** RAF Andover, a former Royal Air Force station

United States

* Ando ...

but his father convinced him to stay in Cambridge to attend Harvard Divinity School

Harvard Divinity School (HDS) is one of the constituent schools of Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts. The school's mission is to educate its students either in the academic study of religion or for leadership roles in religion, gov ...

. There, he was influenced by Levi Frisbie, Professor of Natural Religion, who was largely interested in moral philosophy, which he termed "the science of the principles and obligations of duty". Ripley was becoming very interested in more "liberal" religious views, what he wrote to his mother as "so simple, scriptural, and reasonable". He graduated in 1826. A year later, on August 22, 1827, he married Sophia Dana, a fact which he originally kept a secret from his parents. He asked his sister Marianne to inform them shortly after.

Early career

Ripley officially became a minister at Boston's Purchase Street Church on November 8, 1826, and became influential in the developing the Unitarian religion. These ten years of his tenure there were quiet and uneventful, until March 1836, when Ripley published a long article titled "Schleiermacher

Friedrich Daniel Ernst Schleiermacher (; 21 November 1768 – 12 February 1834) was a German Reformed theologian, philosopher, and biblical scholar known for his attempt to reconcile the criticisms of the Enlightenment with traditional Pr ...

as a Theologian" in the ''Christian Examiner''. In it, Ripley praised Schleiermacher's attempt to create a "religion of the heart" based on intuition and personal communion with God. Later that year, he published a review of British theologian James Martineau

James Martineau (; 21 April 1805 – 11 January 1900) was a British religious philosopher influential in the history of Unitarianism.

For 45 years he was Professor of Mental and Moral Philosophy and Political Economy in Manchester New College ( ...

's ''The Rationale of Religious Enquiry'' in the same publication. In the review, Ripley charged Unitarian church elders with religious intolerance because they forced the literal acceptance of miracle

A miracle is an event that is inexplicable by natural or scientific lawsOne dictionary define"Miracle"as: "A surprising and welcome event that is not explicable by natural or scientific laws and is therefore considered to be the work of a divin ...

s as a requirement for membership in their church.Delano, 5 Andrews Norton

Andrews Norton (December 31, 1786 – September 18, 1853) was an American preacher and theologian. Along with William Ellery Channing, he was the leader of mainstream Unitarianism of the early and middle 19th century, and was known as the "Unitari ...

, a leading theologian of the day, responded publicly and insisted that disbelief in miracle

A miracle is an event that is inexplicable by natural or scientific lawsOne dictionary define"Miracle"as: "A surprising and welcome event that is not explicable by natural or scientific laws and is therefore considered to be the work of a divin ...

s ultimately denied the truth of Christianity. Norton, formerly Ripley's teacher at the Divinity School, had been labeled by many as the "hard-headed Unitarian Pope", and began his public battle with Ripley in the ''Boston Daily Advertiser

The ''Boston Daily Advertiser'' (est. 1813) was the first daily newspaper in Boston, and for many years the only daily paper in Boston.

History

The ''Advertiser'' was established in 1813, and in March 1814 it was purchased by journalist Nathan ...

'' on November 5, 1836, in an open letter charging Ripley with academic and professional incompetence. Ripley contended that to insist upon the reality of miracles was to demand material proof of spiritual matters, and that faith needed no such external confirmation; but Norton and the mainstream of Unitarianism found this tantamount to heresy. This dispute laid the groundwork for the separation of a more extreme Transcendentalism

Transcendentalism is a philosophical movement that developed in the late 1820s and 1830s in New England. "Transcendentalism is an American literary, political, and philosophical movement of the early nineteenth century, centered around Ralph Wald ...

from its liberal Unitarian roots. The debate between Norton and Ripley, which earned allies on both sides, continued until 1840.

Transcendental Club

Ripley met with Ralph Waldo Emerson,Frederic Henry Hedge

Frederic Henry Hedge (December 12, 1805 – August 21, 1890) was a New England Unitarianism, Unitarian minister and Transcendentalism, Transcendentalist. He was a founder of the Transcendental Club, originally called Hedge's Club, and active in ...

, and George Putnam in Cambridge, Massachusetts

Cambridge ( ) is a city in Middlesex County, Massachusetts, United States. As part of the Boston metropolitan area, the cities population of the 2020 U.S. census was 118,403, making it the fourth most populous city in the state, behind Boston, ...

on September 8, 1836, to discuss the formation of a new club.Packer, 47 Ten days later, on September 18, 1836, Ripley hosted their first official meeting at his house. The group at this first meeting of what would become known as the "Transcendental Club The Transcendental Club was a group of New England authors, philosophers, socialists, politicians and intellectuals of the early-to-mid-19th century which gave rise to Transcendentalism.

Overview

Frederic Henry Hedge, Ralph Waldo Emerson, George R ...

" included Amos Bronson Alcott

Amos Bronson Alcott (; November 29, 1799 – March 4, 1888) was an American teacher, writer, philosopher, and reformer. As an educator, Alcott pioneered new ways of interacting with young students, focusing on a conversational style, and av ...

, Orestes Brownson

Orestes Augustus Brownson (September 16, 1803 – April 17, 1876) was an American intellectual and activist, preacher, labor organizer, and noted Catholic convert and writer.

Brownson was a publicist, a career which spanned his affiliation with ...

, James Freeman Clarke

James Freeman Clarke (April 4, 1810 – June 8, 1888) was an American minister, theologian and author.

Biography

Born in Hanover, New Hampshire, on April 4, 1810, James Freeman Clarke was the son of Samuel Clarke and Rebecca Parker Hull, though h ...

, and Convers Francis

Convers Francis (November 9, 1795 – April 17, 1863) was an American Unitarian minister from Watertown, Massachusetts.

Life and work

He was born the son of Susannah Rand Francis and Convers Francis, and named after his father. His sister, Lyd ...

as well as Hedge, Emerson, and Ripley. Future members would include Henry David Thoreau

Henry David Thoreau (July 12, 1817May 6, 1862) was an American naturalist, essayist, poet, and philosopher. A leading Transcendentalism, transcendentalist, he is best known for his book ''Walden'', a reflection upon simple living in natural su ...

, William Henry Channing

William Henry Channing (May 25, 1810 – December 23, 1884) was an American Unitarian clergyman, writer and philosopher.

Biography

William Henry Channing was born in Boston, Massachusetts. Channing's father, Francis Dana Channing, died when he wa ...

, Christopher Pearse Cranch

Christopher Pearse Cranch (March 8, 1813 – January 20, 1892) was an American writer and artist.

Biography

Cranch was born in the District of Columbia. His conservative father, William Cranch, was Chief Judge of the United States Circuit Court ...

, Sylvester Judd

Sylvester Judd (July 23, 1813 – January 26, 1853) was a Unitarianism, Unitarian minister and an American novelist.

Biography

Sylvester Judd III was born on July 23, 1813, in Westhampton, Massachusetts to Sylvester Judd II and Apphia Hall, a daug ...

, and Jones Very

Jones Very (August 28, 1813 – May 8, 1880) was an American poet, essayist, clergyman, and mystic associated with the American Transcendentalism movement. He was known as a scholar of William Shakespeare, and many of his poems were Shakespea ...

. Female members included Sophia Ripley Sophia Willard Dana Ripley (1803–1861), wife of George Ripley, was a 19th-century feminist associated with Transcendentalism and the Brook Farm community.

Biography

She was born Sophia Willard Dana in 1803. Her father traveled abroad often and le ...

, Margaret Fuller

Sarah Margaret Fuller (May 23, 1810 – July 19, 1850), sometimes referred to as Margaret Fuller Ossoli, was an American journalist, editor, critic, translator, and women's rights advocate associated with the American transcendentalism movemen ...

, and Elizabeth Peabody

Elizabeth Palmer Peabody (May 16, 1804January 3, 1894) was an American educator who opened the first English-language kindergarten in the United States. Long before most educators, Peabody embraced the premise that children's play has intrinsic de ...

. The group planned its meetings for times when Hedge was visiting from Bangor, Maine

Bangor ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Maine and the county seat of Penobscot County. The city proper has a population of 31,753, making it the state's 3rd-largest settlement, behind Portland (68,408) and Lewiston (37,121).

Modern Bangor ...

, leading to the early nickname "Hedge's Club". The name Transcendental Club was given to the group by the public and not by its participants. Hedge wrote: "There was no club in the strict sense... only occasional meetings of like-minded men and women", earning the nickname "the brotherhood of the 'Like-Minded'". Beginning in 1839, Ripley edited ''Specimens of Foreign Standard Literature'': fourteen volumes of translations meant to demonstrate the breadth of Transcendental thoughts.

Separation from church

Amid thePanic of 1837

The Panic of 1837 was a financial crisis in the United States that touched off a major depression, which lasted until the mid-1840s. Profits, prices, and wages went down, westward expansion was stalled, unemployment went up, and pessimism abound ...

, many began to criticize social institutions. That year, Ripley gave a sermon titled "The Temptations of the Times", suggesting that the major problem in the country was "the inordinate pursuit, the extravagant worship of wealth". Ripley had been asked by church proprietors to avoid controversial topics in his sermons. He said, "Unless a minister is expected to speak out on all subjects which are uppermost in his mind, with no fear of incurring the charge of heresy or compromising the interests of his congregation, he can never do justice to himself, to his people, or the truth which he is bound to declare". In May 1840, he offered his resignation from the Purchase Street Church but was convinced to stay. He soon decided he should leave the ministry altogether and, on October 3, 1840, he read a 7,300-word lecture, ''Letter Addressed to the Congregational Church in Purchase Street'', expressing his dissatisfaction with Unitarianism.

Because of his experience with the ''Specimens'' translations, Ripley was chosen to be the managing editor of the Transcendental publication ''The Dial

''The Dial'' was an American magazine published intermittently from 1840 to 1929. In its first form, from 1840 to 1844, it served as the chief publication of the Transcendentalists. From the 1880s to 1919 it was revived as a political review and ...

'' at its inception, working alongside its first editor Margaret Fuller. In addition to overseeing distribution, subscriptions, printing, and finances, Ripley also contributed essays and reviews. In October 1841, he resigned his post with ''The Dial'' as he prepared for an experiment in communal living. As he told Emerson, although he was happy seeing all the Transcendental thoughts in print, he could not be truly happy "without the attempt to realize them".

Brook Farm

In the late 1830s Ripley became increasingly engaged in "Associationism

Associationism is the idea that mental process

Cognition refers to "the mental action or process of acquiring knowledge and understanding through thought, experience, and the senses". It encompasses all aspects of intellectual functions and pr ...

", an early Fourierist socialist movement. In October 1840 he announced to the Transcendental Club his plan to form an Associationist community based on Fourier's Utopian plans.Packer, 133 His goals were lofty. As he wrote, "If wisely executed, it will be a light over this country and this age. If not the sunrise, it will be the morning star."

Ripley and his wife formed a joint stock company

A joint-stock company is a business entity in which shares of the company's stock can be bought and sold by shareholders. Each shareholder owns company stock in proportion, evidenced by their shares (certificates of ownership). Shareholders are ...

in 1841 along with 10 other initial investors.Hankins, 34 Shares of the company were sold for $500 apiece with a promise of five percent of the profits to each investor. The founding membership of the original community included Nathaniel Hawthorne

Nathaniel Hawthorne (July 4, 1804 – May 19, 1864) was an American novelist and short story writer. His works often focus on history, morality, and religion.

He was born in 1804 in Salem, Massachusetts, from a family long associated with that t ...

. They chose the Ellis Farm in West Roxbury, Massachusetts

West Roxbury is a neighborhood in Boston, Massachusetts bordered by Roslindale and Jamaica Plain to the northeast, the town of Brookline to the north, the cities and towns of Newton and Needham to the northwest and the town of Dedham to the s ...

as the site of their experiment, which they named Brook Farm

Brook Farm, also called the Brook Farm Institute of Agriculture and EducationFelton, 124 or the Brook Farm Association for Industry and Education,Rose, 140 was a utopian experiment in communal living in the United States in the 1840s. It was f ...

. Its were about from Boston; a pamphlet described the land as a "place of great natural beauty, combining a convenient nearness to the city with a degree of retirement and freedom from unfavorable influences unusual even in the country". The land, however, turned out to be difficult to farm and the community struggled with financial difficulties as it built greenhouse

A greenhouse (also called a glasshouse, or, if with sufficient heating, a hothouse) is a structure with walls and roof made chiefly of Transparent ceramics, transparent material, such as glass, in which plants requiring regulated climatic condit ...

s and craft shops.

Brook Farm was initially based mostly on the ideals of Transcendentalism; its founders believed that by pooling labor they could sustain the community and still have time for literary and scientific pursuits. The experiment meant to serve as an example for the rest of the world, established on the principles of "industry without drudgery, and true equality without its vulgarity". Many in the community wrote of how much they enjoyed their experience. One participant, a man named John Codman, joined the community at the age of 27 in 1843. He wrote, "It was for the meanest a life above humdrum, and for the greatest something far, infinitely far beyond. They looked into the gates of life and saw beyond charming visions, and hopes springing up for all". In their free time, the members of Brook Farm enjoyed music, dancing, card games, drama, costume parties, sledding, and skating. Hawthorne, eventually elected treasurer of the community, did not enjoy his experience. He wrote to his wife-to-be Sophia Peabody, "labor is the curse of the world, and nobody can meddle with it without becoming proportionately brutified".

Many outside the community were also critical, especially in the press. The New York ''Observer'', for example, suggested that, "The Associationists, under the pretense of a desire to promote order and morals, design to overthrow the marriage institution, and in the place of the divine law, to substitute the 'passions' as the proper regulator of the intercourse of the sexes", concluding that they were "secretly and industriously aiming to destroy the foundation of society".

In 1844, the community, perpetually struggling financially, drafted an entirely new constitution and committed to following more closely the Fourierist model. Not everyone at the community supported the transition, and many left. Many were disappointed that the new, more structured daily routine de-emphasized the carefree leisure time that had been a trademark. Ripley himself became a celebrity proponent of Fourierism and organized conventions throughout New England to discuss the community.

By May 1846, troubled by the financial difficulties at Brook Farm, Ripley had made an informal split from the community. By its closure a year later, Brook Farm had amassed a total debt of $17,445.Rose, 136 Ripley was devastated at the failure of his experiment and told a friend, "I can now understand how a man would feel if he could attend his own funeral". His personal life was also taxed. His wife had converted to Catholicism in 1846, encouraged by Orestes Brownson

Orestes Augustus Brownson (September 16, 1803 – April 17, 1876) was an American intellectual and activist, preacher, labor organizer, and noted Catholic convert and writer.

Brownson was a publicist, a career which spanned his affiliation with ...

, and had become doubtful of his Associationist politics; the Ripleys' relationship became strained by the 1850s.Rose, 209

Writing

After Brook Farm, George Ripley began to work as a freelance journalist. In 1849 he was employed by

After Brook Farm, George Ripley began to work as a freelance journalist. In 1849 he was employed by Horace Greeley

Horace Greeley (February 3, 1811 – November 29, 1872) was an American newspaper editor and publisher who was the founder and newspaper editor, editor of the ''New-York Tribune''. Long active in politics, he served briefly as a congressm ...

at the ''New York Tribune

The ''New-York Tribune'' was an American newspaper founded in 1841 by editor Horace Greeley. It bore the moniker ''New-York Daily Tribune'' from 1842 to 1866 before returning to its original name. From the 1840s through the 1860s it was the domi ...

'', taking the role left vacant by Margaret Fuller.Miller, 249 Greeley had been a proponent of Brook Farm's conversion to Fourierism. Ripley started his role with the ''Tribune'' at $12 a week and, at this wage, was not able to pay off the debt of Brook Farm until 1862. As a critic, he believed in high moral standards for literature but offered good-natured praise in the majority of his reviews.Rose, 210 Greeley took advantage of Ripley's cheerful style of writing to boost circulation amid significant competition. Ripley wrote a "Gotham Gossip" column and many articles discussing local personalities and notable public events, including speeches by Henry Clay

Henry Clay Sr. (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American attorney and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives. He was the seventh House speaker as well as the ninth secretary of state, al ...

and Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he became ...

. He stayed away from philosophy of theology, despite some efforts to persuade him to write on the subject. As he told a friend, he had "long since lost... immediate interest in that line of speculation".

Ripley then edited ''Harper's Magazine

''Harper's Magazine'' is a monthly magazine of literature, politics, culture, finance, and the arts. Launched in New York City in June 1850, it is the oldest continuously published monthly magazine in the U.S. (''Scientific American'' is older, b ...

''. Together with Bayard Taylor

Bayard Taylor (January 11, 1825December 19, 1878) was an American poet, literary critic, translator, travel author, and diplomat. As a poet, he was very popular, with a crowd of more than 4,000 attending a poetry reading once, which was a record ...

he compiled a ''Handbook of Literature and the Fine Arts'' (1852).

With Charles A. Dana, he edited the 16 volume ''The New American Cyclopaedia'' (1857–1863), reissued as ''The American Cyclopaedia'' (1873–1876). It sold in the millions and its immediate earnings amounted to over $100,000.

He also continued his critical work and in 1860 reviewed ''On the Origin of Species

''On the Origin of Species'' (or, more completely, ''On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life''),The book's full original title was ''On the Origin of Species by Me ...

'' by Charles Darwin

Charles Robert Darwin ( ; 12 February 1809 – 19 April 1882) was an English naturalist, geologist, and biologist, widely known for his contributions to evolutionary biology. His proposition that all species of life have descended fr ...

. He was one of the few contemporary critics to be sympathetic to Darwin, although he was reluctant to show he was convinced of the theories.

Later years

In 1861 Sophia Ripley died. George Ripley remarried, to Louisa Sclossberger, in 1865, and was a part of theGilded Age

In United States history, the Gilded Age was an era extending roughly from 1877 to 1900, which was sandwiched between the Reconstruction era and the Progressive Era. It was a time of rapid economic growth, especially in the Northern and Weste ...

New York literary scene for the remainder of his life. Because of his convivial nature, he was careful to avoid the city's rampant literary feuds at the time. He became a public figure with a national reputation and, known as an arbiter of taste, he helped establish the National Institute of Literature, Art, and Science in 1869. In his later years, he began suffering frequent illnesses, including a bout with influenza

Influenza, commonly known as "the flu", is an infectious disease caused by influenza viruses. Symptoms range from mild to severe and often include fever, runny nose, sore throat, muscle pain, headache, coughing, and fatigue. These symptoms ...

in 1875 which prevented him from traveling to Germany. He also suffered from gout

Gout ( ) is a form of inflammatory arthritis characterized by recurrent attacks of a red, tender, hot and swollen joint, caused by deposition of monosodium urate monohydrate crystals. Pain typically comes on rapidly, reaching maximal intensit ...

and rheumatism

Rheumatism or rheumatic disorders are conditions causing chronic, often intermittent pain affecting the joints or connective tissue. Rheumatism does not designate any specific disorder, but covers at least 200 different conditions, including art ...

.

Ripley was found dead at his desk on July 4, 1880, slumped over his work. Pallbearers at his funeral included Frederick Augustus Porter Barnard

Frederick Augustus Porter Barnard (May 5, 1809 – April 27, 1889) was an American academic and educator who served as the 10th President of Columbia University. Born in Sheffield, Massachusetts, he graduated from Yale University in 1828 and serv ...

, George William Curtis

George William Curtis (February 24, 1824 – August 31, 1892) was an American writer and public speaker born in Providence, Rhode Island. An early Republican, he spoke in favor of African-American equality and civil rights both before and after ...

, and Whitelaw Reid

Whitelaw Reid (October 27, 1837 – December 15, 1912) was an American politician and newspaper editor, as well as the author of ''Ohio in the War'', a popular work of history.

After assisting Horace Greeley as editor of the ''New-York Tribu ...

. At the time of his death, Ripley had become financially successful; the ''New American Cyclopaedia'' had earned him royalties of nearly $1.5 million. A biography entitled George Ripley

' (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin & Co., 1882) was written by

Octavius Brooks Frothingham

Octavius Brooks Frothingham (November 26, 1822 – November 27, 1895) was an American clergyman and author.

Biography

He was born in Boston, Massachusetts, the son of Nathaniel Langdon Frothingham (1793–1870), a prominent Unitarian preacher, ...

.

Critical assessment

Ripley built a wide reputation as a critic. Contemporary publications rated him as one of the most important critics of the day, including the ''Hartford Courant

The ''Hartford Courant'' is the largest daily newspaper in the U.S. state of Connecticut, and is considered to be the oldest continuously published newspaper in the United States. A morning newspaper serving most of the state north of New Haven ...

'', the ''Springfield Republican

''The Republican'' is a newspaper based in Springfield, Massachusetts covering news in the Greater Springfield area, as well as national news and pieces from Boston, Worcester and northern Connecticut. It is owned by Newhouse Newspapers, a ...

'', the New York '' Evening Gazette'', and the ''Chicago Daily Tribune

The ''Chicago Tribune'' is a daily newspaper based in Chicago, Illinois, United States, owned by Tribune Publishing. Founded in 1847, and formerly self-styled as the "World's Greatest Newspaper" (a slogan for which WGN radio and television are ...

''. Henry Theodore Tuckerman

Henry Theodore Tuckerman (April 20, 1813 – December 17, 1871) was an American writer, essayist and critic.

Early life

Henry Theodore Tuckerman was born on April 20, 1813, in Boston, Massachusetts.

His first cousins included Edward Tuckerman ( ...

commended Ripley as "a scholar and an aesthetic as well as technical critic: eknows public taste and the laws of literature".England, 231

References

Sources

*Buell, Lawrence. ''Emerson''. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2003. *Crowe, Charles. ''George Ripley: Transcendentalist and Utopian Socialist''. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1967. *Delano, Sterling F. ''Brook Farm: The Dark Side of Utopia''. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2004. *Ehrlich, Eugene and Gorton Carruth. ''The Oxford Illustrated Literary Guide to the United States''. New York: Oxford University Press, 1982. *England, Eugene. ''Beyond Romanticism: Tuckerman's Life and Poetry''. New York: SUNY Press, 1991. *Felton, R. Todd. ''A Journey into the Transcendentalists' New England''. Berkeley, California: Roaring Forties Press, 2006. *Golemba, Henry L. ''George Ripley''. Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1977. *Gura, Philip F. ''American Transcendentalism: A History''. New York: Hill and Wang, 2007. *Hankins, Barry. ''The Second Great Awakening and the Transcendentalists''. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2004. *McFarland, Philip. ''Hawthorne in Concord''. New York: Grove Press, 2004. *Miller, Perry. ''The Raven and the Whale: Poe, Melville, and the New York Literary Scene''. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1997 (originally published 1956). *Packer, Barbara L. ''The Transcendentalists''. Athens, Georgia: The University of Georgia Press, 2007. *Rose, Anne C. ''Transcendentalism as a Social Movement, 1830–1850''. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press: 1981. *Slater, Abby. ''In Search of Margaret Fuller''. New York: Delacorte Press, 1978.External links

*George Ripley, Charles A. Dana''The American Cyclopaedia.''

From

Internet Archive

The Internet Archive is an American digital library with the stated mission of "universal access to all knowledge". It provides free public access to collections of digitized materials, including websites, software applications/games, music, ...

.

Ripley biography

from ''Dictionary of Unitarian & Universalist Biography''

from Alcott School

from Transcendentalism Web *

Collection Guide to Ripley's scrapbooks

at Harvard University {{DEFAULTSORT:Ripley, George Founders of utopian communities Members of the Transcendental Club American Unitarians Harvard Divinity School alumni 1802 births 1880 deaths People from Greenfield, Massachusetts American social reformers American Christian socialists Unitarian socialists Utopian socialists People from West Roxbury, Boston